Narendra Kusnur writes:

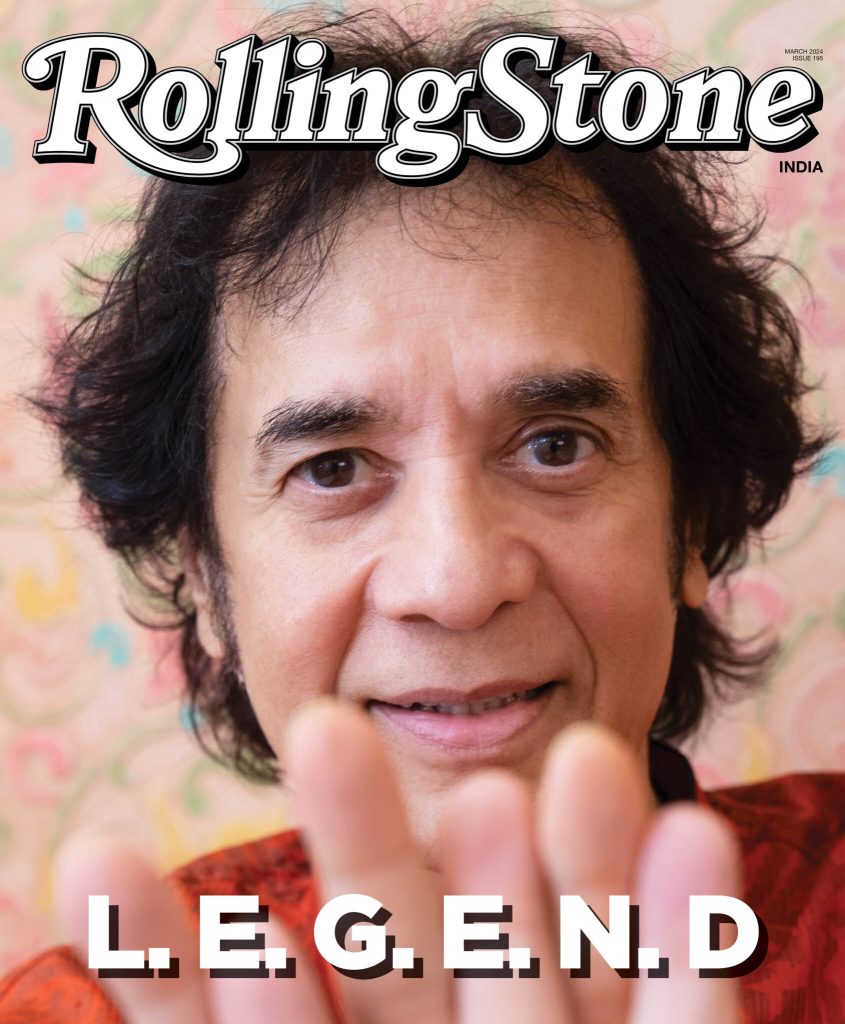

He will turn 73 in March and he has just won three Grammys. But that is not going to slow down the maestro. Ustad Zakir Hussain is as busy with his Hindustani classical and fusion projects as he was when he started his career nearly six decades ago

Movement 1 – Theka

For tabla virtuoso Ustad Zakir Hussain, who will turn 73 this month, the decision to attend the Grammy Awards ceremony in Los Angeles on February 4th was taken at the last minute. Both he and guitarist John McLaughlin, who had co-founded the Indo-jazz fusion group Shakti in 1973, had other commitments. Hussain managed to juggle his schedule and was delighted to be present at the prestigious event.

The new Shakti album This Moment went on to win the Best Global Music Album award. Hussain won two other Grammys for the album As We Speak, featuring banjo player Bela Fleck, bassist Edgar Meyer, and flautist Rakesh Chaurasia. It won the Best Global Music Performance award for the song “Pashto,” and the Best Contemporary Instrumental Album. He thus became the first Indian artiste to pick up three Grammys in a single night. He had earlier played an active part in the Grammy-winning albums Planet Drum (1991) and Global Drum Project (2008), spearheaded by Mickey Hart, drummer of the rock band Grateful Dead.

Interestingly, because of an unexpected development, the Padma Vibhushan recipient could not personally collect the Shakti award. He explains, “The award for ‘Pashto’ was announced first. I wasn’t expecting it at all, and since I hadn’t prepared a thank you speech, I ended up mumbling something randomly. Bela couldn’t attend the ceremony and as per the procedure, Edgar, Rakesh, and I went backstage to give bytes to the media. While that was happening, the Shakti award was announced, and I was clueless. It was only befitting that the younger generation of Shakti musicians—vocalist Shankar Mahadevan, violinist Ganesh Rajagopalan, and kanjira player V. Selvaganesh—collected the award.”

The Shakti award comes after the group completed its 50th-anniversary tour, covering India, the U.S., and Europe. Hussain says this recognition was well-deserved, considering that it was Shakti’s first studio album after 46 years. “When we released A Handful Of Beauty and Natural Elements in the 1970s, the category of World Music didn’t exist. When we came back in the 1990s as Remember Shakti, we focused on live performances. The new Shakti album just happened when all of us were in different places during the pandemic and wanted to create something new. There has been a huge change in the content, with more vocals now,” he says.

Last year also marked 50 years since Hussain worked on ex-Beatle George Harrison’s album Living In The Material World. Declares Hussain, “I have always believed that Shakti and the George Harrison album, along with the Taj Mahal Tea ad, played a major role in expanding my audience.”

Movement 2 – Peshkar

Over the years, Hussain has been known to maintain a balance between traditional music and experimentation. Besides his father, the list of legends he has accompanied on stage over the last five decades reads like a who’s who of Indian classical music — Pandit Ravi Shankar, sarod masters Ustad Ali Akbar Khan, and Ustad Amjad Ali Khan, santoor great Pt Shivkumar Sharma, flautist Pt Hariprasad Chaurasia, vocalists Pandit Jasraj, Kishori Amonkar and dozens of others both from Hindustani and Carnatic streams. He also accompanied Kathak legend Pt Birju Maharaj and thumri doyenne Shobha Gurtu. Besides the sheer brilliance of his playing, his charisma and stage presence has ensured that he is the best-known of the living tabla maestros. Besides the traditional rhythmic patterns of the Punjab gharana which he represents, his stage performances are often punctuated with a display of spontaneous sense of humor. He would sometimes play popular pieces like “Doe A Deer,” “Smoke On The Water” and “Ek Do Teen,” and even replicate the sound of horses or railway trains.

Born on March 9th, 1951, the eldest son of legendary tabla maestro Ustad Alla Rakha and Bavi Begum began learning the instrument from a very young age. He has often told the story about the basic rhythm of the tabla being the first words his legendary father whispered into his ears when he was first brought home after birth by his mother. The name Zakir refers to someone performing zikr, a form of devotion that involves rhythmically repeating Allah’s name. The family name was Qureshi, and the young lad grew up in Mahim, Mumbai, where he attended St Michael’s School. Early mornings were spent learning and practicing rhythmic syllables or bols.

A child prodigy, Hussain started touring when he was 12. By the time he was in his mid-teens, the following for Indian music had increased considerably in the West, thanks to Pt Ravi Shankar and Ustad Ali Akbar Khan. On tours, they were accompanied on tabla by Ustad Alla Rakha and Pandit Chatur Lal, who passed away in 1965.

In 1968, Ravi Shankar won the Best Chamber Music Performance award for West Meets East, his collaboration with violinist Yehudi Menuhin. For his part, Alla Rakha collaborated with American jazz drummer Buddy Rich on the album Rich A La Rakha. These projects opened the possibility of Indian musicians collaborating with western artists.

With sitar players Harihar Rao and Ananda Shankar, and jazz players John Henry Mayer, John Handy and Joe Harriott fusing Indian music with jazz and orchestral music, the stage had been set for Indo-fusion. This genre was inspired by jazz-rock fusion, which had become popular among younger listeners.

It was around this time that McLaughlin first met Hussain in New York, in 1969. Mclaughlin was already famous by then as one of the most proficient jazz guitarists in the business, having played alongside the likes of Miles Davis, Wayne Shorter, Larry Coryell, Jaco Pastorius as well as rock greats like Carlos Santana, Jimi Hendrix, the Rolling Stones etc. He would also become famous in the 1970s for getting together two pioneering jazz fusion bands around that time—the Mahavishnu Orchestra with Jerry Goodman, Jan Hammer, Rick Laird and Billy Cobham; and the lesser-known Trio of Doom with Tony Williams and Jaco Pastorius.

In 1970, Mclaughlin met spiritual leader Sri Chinmoy which led to his deepening interest in Indian classical music. He and Hussain played together for the first time in 1972 at the house of Ustad Ali Akbar Khan in California. The guitarist also met violinist L Shankar a few months later, which resulted in the idea of forming Shakti, with Vikku Vinayakram joining on ghatam. Mridangam exponent Ramnad Raghavan accompanied them on two shows. Hussain recalls, “Meeting John ji was a pivotal moment in my life, him accepting me as a colleague was a milestone moment for me. It was indeed the time when everything changed going forward for me.”

Shakti became a resounding success. However, because each musician had other commitments, they toured only at certain times of the year. Says Hussain, “That made it a bit easier for me to balance my teaching assignment at the Ali Akbar College in San Francisco. I was also playing concerts with Khansaheb and he was concerned, as were my father and Ravi Shankar ji, that I would neglect my classical performances. But I was very focused on keeping my Indian classical life in the forefront. It was also helpful that Shakti did not tour India when it was first formed.”

It would be 1982 when Shakti first came to India, that too with guitarist Larry Coryell, filling in for McLaughlin who had an injured hand. A second tour came soon after, in 1984 with Mclaughlin back in the band. It was a massive success, and attracted many new fans here. However, the quartet stopped playing in the mid-1980s when Vinayakram had to manage his father’s school in Chennai, and Shankar got involved in other projects.

They were to return as Remember Shakti in 1997, with flautist Pt Hariprasad Chaurasia and saxophonist Bendik Hofseth coming in place of Shankar. Later, mandolin wizard U. Srinivas, Selvaganesh and Mahadevan were to join McLaughlin and Hussain. Their album Saturday Night In Bombay, recorded live at the erstwhile Rang Bhavan in 2000, was a fan’s delight.

Hussain always had a Carnatic percussionist for company in Shakti, first in the form of Vinayakram, then Selvaganesh. As he says, “That was an advantage, as I did not have to radically alter my thinking process. Vikku ji was fabulous to work with, and there was no divide or fences from the very first day. I learnt a lot of taal vidya from the great man. In the early days, John ji and Shankar would allow me and Vikku ji to come up with the rhythmic element to support the compositions, and we thought of korvais and rhythmic transitions which John ji would incorporate. Playing with Selva bhai was great fun too. He had grown up on Shakti and is an extension of Vikku ji. That works perfectly.”

His work with Carnatic musicians have extended beyond Shakti in recent times. A few years ago, he teamed up with violinist Kala Ramnath and veena exponent Jayanthi Kumaresh to successfully tour around the world as Triveni.

Movement 3 – Sawaal-jawaab

Hussain’s desire to experiment led to various other projects. He contributed to albums by Irish singer Van Morrison and the group Earth Wind & Fire, and formed the Diga Rhythm Band with Mickey Hart, which also included the legendary Grateful Dead guitarist Jerry Garcia on two songs “Rasooli” and “Happiness Is Drumming.” Hussain’s 1986 album Making Music featured McLaughlin, Chaurasia, and Norwegian saxophonist Jan Garbarek. It contained a tune called “Zakir,” co-written by McLaughlin. In 1990, he was part of Hart’s project Planet Drum, along with Vinayakram, Sikiru Adepoju and Babatunde Olatunji of Nigeria, Giovanni Hidalgo and Frank Colon of Puerto Rico, and Brazilian percussionist Airto Moreira and his wife Flora Purim.

Little known is the fact that he occasionally ventured into acting — in James Ivory’s Heat & Dust (1983) and Sai Paranjpye’s Saaz (1997). Hussain has recently spoken about the fact that in the late 1950s, on the suggestion of Dilip Kumar, he was offered the role of the young Prince Salim in Mughal-e-Azam by director K. Asif. But the potential film debut never materialized because his father objected, saying that he will only be a musician. His most famous celluloid appearance of course has been the long-running Taj Mahal Tea commercial, which made‘Wah Taj!’ a household catchphrase.

Hussain has also composed for Aparna Sen’s Mr & Mrs Iyer. Thematic albums like Soundscapes: Music Of The Deserts and The Elements: Space expanded his repertoire, and collaborations with guitarist Pat Martino, saxophonists Charles Lloyd, Chris Potter and George Brooks, and bassist Dave Holland lent more variety to his playing. He even did a guest appearance with ace keyboardist Joe Zawinul’s Syndicate at Rang Bhavan in 1997.

In the late 1990s, the Asian Underground movement had picked up in the U.K., where young musicians created songs blending Asian flavors with modern electronic music. In keeping with the trend, Hussain joined producer Bill Laswell on the project Tabla Beat Science, blending Indian percussion with Asian Underground, drum and bass and electronica. At the other end of the spectrum, he was commissioned by the National Centre for the Performing Arts’ (NCPA’s) Symphony Orchestra of India (SOI) in 2015 to compose the Peshkar Concerto for Tabla & Orchestra, conducted by Zane Dalal. Last year, he composed the Triple Concerto for Tabla, Sitar and Flute, with Niladri Kumar and Rakesh Chaurasia as soloists, with Alpesh Chauhan conducting the SOI in the opening shows.

According to Hussain, composing a piece with a western classical orchestra in mind requires a completely different mindset. “It’s a different ceiling. One has to adapt to the rules of their playing, their dos and don’ts, while maintaining the Indian classical form,” he says. Hussain adds, “Moreover, being a percussionist has its own challenges as normally a melody instrument is used. But in Peshkar, I used the same concept I use in my solo performances. The Triple Concerto is based on the concept of canon.”

In global fusion, Hussain has performed often with Fleck and Meyer, and they even performed at the Barsi concert in Mumbai, held annually as a homage to Ustad Alla Rakha. “We did the album The Melody Of Rhythm in 2009. For the new album, Rakesh Chaurasia joined us. ‘Pashto,’ which got the award, is inspired by a British military tune in the North-West Frontier Province of India played by both marching soldiers and Indian musicians,” says Hussain.

Movement 4 – Kaayda

While his father was among the first to introduce the tabla to the European and American audience, mesmerizing them with his unparalleled wizardry, Hussain has over the years taken that work forward. In the manner that Ravi Shankar has done for the sitar, he has helped popularize the Indian percussion instrument across at least two generations of audiences around the world. Though he grew up in an era that had many brilliant tabla artistes like Anindo Chatterjee, the late Shafaat Ahmed Khan, Kumar Bose, and Swapan Chaudhuri, he has created a new audience through innovations and collaborations. His younger brother Fazal Qureshi took to the tabla too, and now trains students at the Ustad Alla Rakha Institute of Music. The third brother Taufiq Qureshi has adapted the African djembe to the Indian style and has done some amazing live shows.

According to Hussain, today’s young generation has a lot more tabla players because there are more avenues to learn. “I see some of these youngsters and looking at their speed and accuracy, my jaw drops,” he says. “Today’s tabla players have all the information from a much earlier age. Because of technology, young players have access to different techniques which took people from my generation a longer time to figure out. Yet, one must master the traditional style first, because they are the roots of more modern styles. The same is the case with both western and Indian classical music. Only if you know the traditional form, you can do film music, ghazal, fusion,” he adds.

The maestro says that as tabla artistes, the main role is that of being an accompanist. “I see many youngsters wanting to get straight into solo concerts, but they should be able to play with different formats. Within classical music, there are different layers. Playing with a vocalist has one style, playing with a sitar player another, and along with santoor or bansuri requires a completely different skill set. So, besides the tabla, one should get into intricacies of other instruments, or even how dance forms or vocal styles like thumri or ghazal are performed. One also needs to know the components of an orchestra,” he adds.

Movement 5 – Tihai

Hussain points out that besides his father—who passed away in February 2000—and McLaughlin, he has had great times with Pandit Shivkumar Sharma, Pandit Hariprasad Chaurasia, and sarangi maestro Ustad Sultan Khan. “My father always insisted on the importance of being a good student. The moment you decide you are a maestro or an Ustad, you are distancing yourself from the others. You have to be part of a group, and not dominate it,” he points out.

Talking of his special bond with Shivkumar Sharma, who passed away in May 2022, Hussain says, “We played hundreds of concerts, and had hundreds of conversations, that extended from music to spirituality and history to politics and whatever. After he passed away, I [did] a few shows with his son Rahul Sharma, and certain stage mannerisms and playing techniques of Rahul remind me of Shiv ji, making me look towards the sky and ask for Shiv ji’s blessings. When I play with younger artistes like Niladri, Rakesh, and Rahul, there are many things I gain from the interaction. They also have an understanding of how the western system functions.”

Asked what advice he would give to the younger generation, Hussain cites three things. “The first is to take pride in what one does, and not to think of tabla playing as a chore or a kind of job. Secondly, listen to everything. Having an open ear helps one discover things much more easily. Finally, one has to move with the times, and keep oneself relevant. I myself wouldn’t like to be called a relic.”

The tabla maestro is now looking forward to some exciting projects this year. “After the Grammys, I returned to do some concerts in Mumbai, Pune, and Bengaluru. It’s heartening to see packed halls where I play. I think there has been a listening renaissance all over the world. Today, people like to go out, and attending music programmes is part of their plan,” he says.

Lined up this year are an As We Speak tour and multiple concerts with sarangi player Sabir Khan and flutist Debopriya Chatterjee. He is also writing some music for the Third Coast Percussion Ensemble of the U.S. “That’s another challenge, as besides regular percussion instruments, I will be composing for xylophones and vibraphones. I have received some offers to write for films, but things are yet to be finalized.” Clearly, Hussain seems to be enjoying every bit of the action. For thousands of fans, there’s never a shortage of surprises. The beat goes on.

Read the full article in Rolling Stone.